IEEFA: If Chevron, Exxon and Shell can’t get carbon capture right at Gorgon, who can?

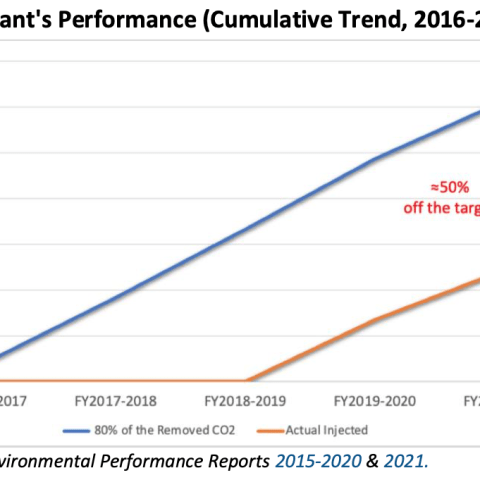

According to a IEEFA (Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis) report, Gorgon, the largest carbon capture and storage (CCS) project in the world, has failed to deliver, underperforming its targets for the first five years of operation by about 50%.

At a cost of more than A$3 billion, Gorgon, the largest carbon capture and storage (CCS) project in the world has failed to deliver, underperforming its targets for the first five years of operation by about 50%, according to a new report from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

Carbon capture technology has historically been used as a method of enhanced oil recovery (EOR) – selling captured CO2 to oil companies to push more oil out of depleted wells, making any initial “carbon capture” negligible. According to the Global CCS Institute, about 73% of carbon capture globally is currently used for EOR projects – called Carbon Capture Utilisation and Storage (CCUS).

In some newer projects like Western Australia’s Gorgon CCS, instead of being sold for EOR, the captured CO2 is sequestered in dedicated geological storage structures.

Although Gorgon’s gas plant produced its first LNG cargo in March 2016, the first CO2 injection from its CCS facility occurred in August 2019 – three and a half year late. The Gorgon CCS project was initially planned to capture and inject underground up to 4 million tonnes (MT) of reservoir CO2 each year from the extraction and production of reservoir gas. Instead, the project sequestered on average less than 1MT pear year.

“Gorgon CCS failed to reach its pre-defined targets,” says report author LNG/gas analyst Bruce Robertson. “CCS technology has been operating for 50 years. If Chevron and its partners can’t get it to work these past 5 years at Gorgon, it’s not an effective technology for reducing carbon emissions.”

Gorgon recently agreed to buy and surrender credible greenhouse gas offsets recognised by the West Australian Government to offset its target shortfall of 5.23 million tonnes of CO2.

“It has been estimated that it would cost up to US$184 million for Chevron and its partners to offset that shortfall,” says Robertson.

In March 2022, the upward trend of Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCU) spot price reversed to a plunge when the Federal Government proposed a policy change which allowed previously contracted offset projects to be terminated. This consequently let a huge number of carbon offsets enter the open market.

The sudden reduction in price created an opportunity for big polluters like Chevron to offset its emissions shortfall by paying around US$100 million less, if it planned to source all the required offsets from the Australian market.

“Either way, such an offset cost is an expensive outcome for a A$3+ billion investment. And will particularly affect taxpayers, as the liability of the project will be handed to government in the long-run.”

IEEFA report: Gorgon is inefficient in capturing carbon

Co-author of the report energy analyst Milad Mousavian notes that Gorgon’s frequent inefficiencies, and problems that led to underperformance in capturing carbon and injecting it, are typical of the technical risks involved in CCS projects.

“Despite the technology being in use since the 1970s, each CCS project appears to have unique difficulties and uncertainties,” he says. “Apart from the credibility of carbon credits in offsetting emissions being under question, Gorgon’s underperformance in meeting its emission targets has brought about a material cost for Chevron and its major partners ExxonMobil and Shell.”

Robertson notes despite mounting evidence, governments around the world are considering subsidized investments for CCS and CCUS projects as emission reduction solutions.

“When an energy technology is consistently shown not to work, but can attract subsidies, you can be sure there are lobbyists and greenwashing at play,” he says. “The oil and gas industry are harvesting subsidies to prolong the life of their operations, not for emissions reduction.” Robertson notes the extent of emissions are from the oil and gas industry, from production to consumption, are becoming increasingly apparent, despite the industry’s downplaying.“Emissions from oil and gas are higher when the fuel is burnt than when it is produced. Governments and investors are focusing on a partial problematic solution by trying to capture carbon at the production end,” he says. “The emissions unaccounted for – the Scope 3 emissions – are where the big problem lies if countries are to reach their zero carbon goals and align the world with 1.5 degrees C.”

Mousavian says there are proven methods already available for reaching net zero carbon. “While CCS is technically feasible in some cases, the numbers don’t add up and the commercial realities are not promising. CCS and CCUS with EOR is all about more fossil fuels, not lowering emissions. Rather than continuing with fossil fuels and the technological impracticalities of trying to capture their pollution, governments and investors must address the root cause, and limit fossil production. Urgent investment in renewable energy and storage technologies is the cheaper and proven pathway going forward.”