Renewable energy growth, a bright spot on a gloomy horizon

This article by 10 Billion Solutions explores the vital role renewable energy can play in mitigating the effects of the climate emergency. The article highlights the rapid growth of renewable energy, including solar, wind, and hydroelectric power, and its potential to reduce carbon emissions and transition towards a sustainable future. At a time when the world is grappling with the effects of the climate emergency, this article presents a ray of hope, showcasing how renewable energy can drive progress towards a more sustainable future.

Multiple mega-threats seem to loom larger and darker by the week: climate change, inflation, social inequalities, pandemics and, last but not least, the steady escalation in the geopolitical confrontations between nuclear powers. In this bleak landscape, the growth of renewable energy shines as a beacon of hope for the rapid decarbonisation of our economies. But is that rapid enough?

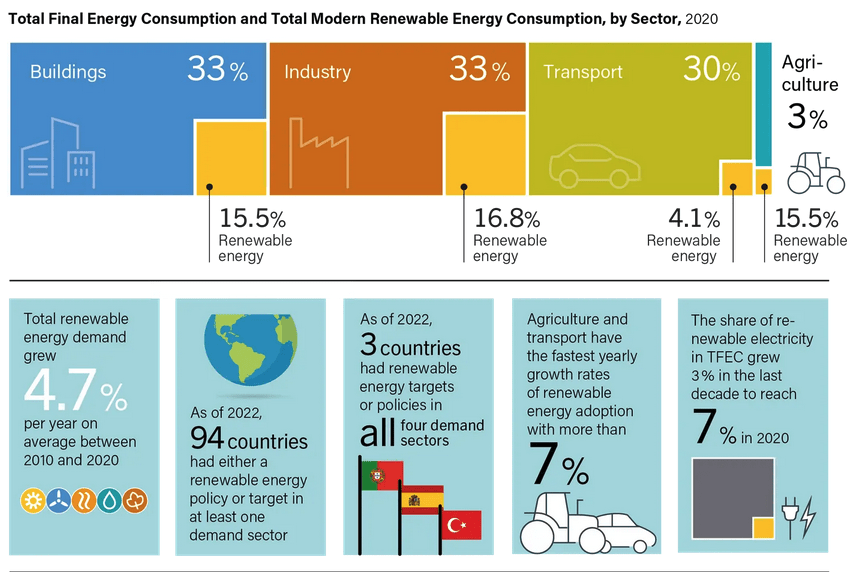

The world is still running mainly on fossil fuels. 80% of the global energy supply comes from burning oil, gas and coal, and only 12% comes from renewables (mainly hydro, wind and solar).

Although renewable energies are growing very fast, the global energy demand is progressing too. Therefore, the new clean energy installed does not come as a clear substitute but rather an addition to fossil fuels in the global energy mix.

Renewable energy: where is the good news?

The good news these days comes mainly from the electricity sector, which is going green even faster. In 2022, around 27% of the world’s electricity came from renewables (hydro, wind or solar), according to a recent report published by the think tank Ember (the International Energy Agency’s numbers are to be published in October).

Still, electricity accounts for only 20% of the world’s energy consumption, and most of human activities (transport, heating, industry…) are still largely running on liquid, gas and solid fossil fuels that have caused and keep worsening the climate crisis.

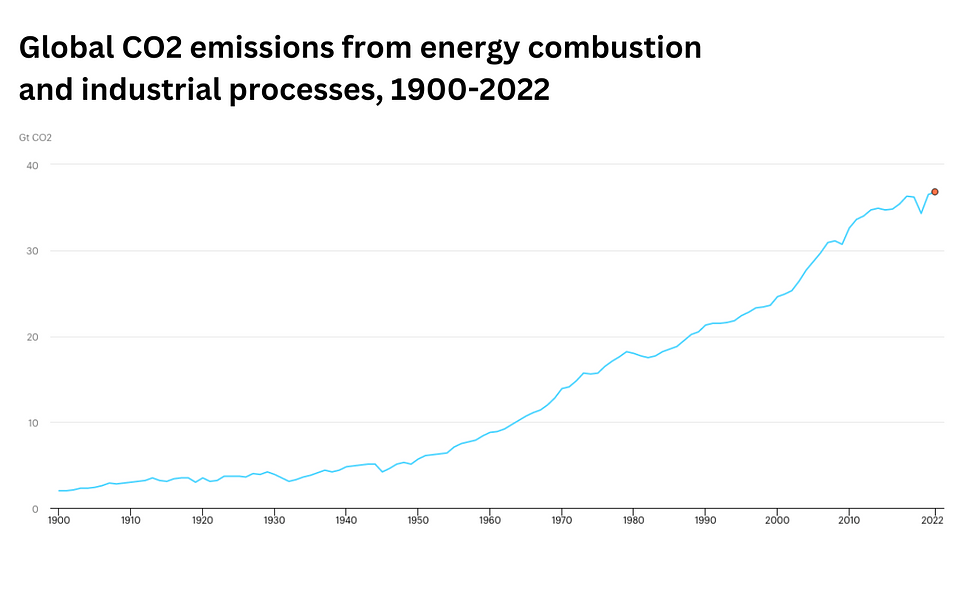

The world is not yet reducing greenhouse gas emissions as agreed by nations in the Paris Agreement, with the objective of keeping humanity relatively safe from climate chaos.

In March, the IPCC sounded the alarm again, reminding us of the urgency of reducing consumption, improving energy efficiency and shifting to cleaner sources of energy if we want to avoid the most catastrophic climate impacts.

In the last year, renewable energy kept growing very rapidly, pushed by the state of poly-crisis we have lived in since 2020, as explained by REN21 in its recent Renewable Energy Global Status Report 2023.

The best news in the report is that top energy user sectors – buildings, industry, transport, and agriculture – are increasing their uptake of renewable energy (RE) at an unprecedented rate.

The recent Spanish International Renewable Energy Conference SPIREC in Madrid, introduced what is shaping to become the “Year of Renewables”. Experts, industry representatives and policymakers from more than 100 countries debated the five key tracks component of the energy transition: supply, demand, economy, society and innovation.

An overarching theme was the focus on citizens and communities – “Renewables for People”–, the energy transition indeed must be centred first on the vital interests of humans and on contributing to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals, with a particular focus on SDG 7: affordable and clean energy for all.

What does the clean energy revolution require?

Huge momentum has built up for Renewables, fed by a strong sense of urgency and key advances in technological and economic features of producing & storing non-fossil fuels energy. Will this momentum translate into the true revolution that is required in this context of a race against the clock against the climate emergency, or merely an evolution? The tremendous progress in renewable energy and related technologies make transitioning to a low-emission economy far easier, and economically very sensible. The question no longer is “whether” or “if”, but “how soon”.

Geopolitical shifts, alongside all the risks and chaos they are generating, are a vector for massive Renewable Energy transition. In particular (but far from only) in Europe, the war in Ukraine has deeply reshuffled energy strategies, with a new and acute need for national energy security and autonomy. Renewables are obviously a trump card in progressing towards this security; after coal and fossil gas have spiked initially, renewables keep growing in relative shares of the energy mix. However, this must not hide the fact that, at the present time, the use of fossil fuels continues to grow at least as fast as a result of sharply increasing global demand.

Electrification is a must in as many areas of our economies as possible – heating & cooling, industry, agriculture, transportation, etc. Although electrification eliminates the burning of fossil fuels at the point of consumption, it is necessary that the electricity itself comes from renewable sources so that electrification does not lead to a “delocalization” of pollution.

De-centralize & democratise the production of energy and re-localize industries close to new distributed energy sources. Renewables technology enables this shift away from a few dominant companies to a very granular network of energy providers of all sizes. The promise of homes, companies or cities generating their own power doesn’t come without its own challenges, however: witness those encountered in the United States. We find an example in the US. electricity grid, or rather the access to it, and its complex regulatory system, were not designed to handle the sudden influx of new energy sources; as a consequence, simply getting permission to connect to the grid can take years. This currently discourages a massive proportion of projects; fewer than one-fifth of solar and wind proposals actually make it through the so-called interconnection queue, according to research from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Look beyond the spot solutions that use Renewable Energy and consider the full supply chains when assessing decarbonisation potential. A classic example is the electric car, which doesn’t emit CO2 while moving, but which parts have been produced in very large part using fossil fuels as energy sources (steel, mining rare earth for batteries, plastics, etc.).

Social acceptance is key; the narrative around Renewable Energy must be compelling and federate all stakeholders in societies. It also must be inclusive and just, to make acceptable the deep shifts in energy production, modes of consumption and conservation that are required. For instance, there is a constant and sharp increase in overall energy demand. Most of this demand is, of course, legitimate, particularly in developing countries, but in rich countries, should this increase be considered a given, or should higher sensitivity be introduced to distinguish between fundamental needs and those which are not so? A societal definition and acceptance of what energy sobriety means will probably be required, along with fair & just access to energy.

Political impetus will remain vital – renewable energy will be central to achieving carbon neutrality, and persistent political steering will be paramount to ensure carbon neutrality pledges are aligned to the IPCC’s recommendations, broken down between short, interim and long-term targets, and subjected to clear transition plans. This needs to happen in lockstep with a phasing out of government subsidies to fossil fuels, which have peaked during this current energy crisis. Governmental policies (hopefully well-harmonized across nations) must become the backbone of those plans. In this respect, Spain, which hosted SPIREC, has been a clear pacesetter in driving the renewable energy sector growth for a long time already. It has demonstrated strong governance in setting clear targets in this domain and ensuring the execution of those plans happens. This allowed Spain to have the 8th largest installed renewable capacity in the world, and the second largest in Europe, with renewables accounting for just below half of electricity generation in Spain. The country also leads in renewables R&D and manufacturing capabilities for wind and photovoltaic power.

The role of public policy in accelerating this transition cannot be overstated — to push our societies over the tipping point into a sustainable economy, one that finally decarbonises at scale. With the enormous progress on Renewables and their new economic attractiveness, huge amounts of public money are not needed, but enough to act as a catalyst for change and to encourage private investment.

To be sure, the path to full-throttle progress in clean energy remains steep, as illustrated by the International Energy Agency’s clean energy tracker. However, never before has there been so much basis for believing that this is possible, not only because of the progress of classic renewables such as solar and wind power but also in alternative energies. Take the example of natural hydrogen that could be drilled instead of produced from methane or from water, which requires high amounts of electricity. We could leverage the infrastructures and know-how from the traditional fossil fuel industries for the exploration, production, and transportation of clean hydrogen. There may be hundreds of millions of megatons of hydrogen in Earth’s crust, and even if only 10 % of it is accessible, that will meet the demand for hundreds of years at the current rate of consumption.

Yet, this hidden hydrogen is still prospective, as nuclear fusion is, while existing renewables technology – deployed at a much greater scale and paired with a boost to energy efficiency – is already more than enough to make the profound energy shift away from fossil fuels the world urgently needs.